By Karen Knapstein

The California-based Warrior Village Project is an effort to alleviate the problem of homeless veterans. Founder Mark Pilcher says the idea for the project was inspired by connecting two problems: the serious homelessness and housing affordability problem and the shortage of students coming out of schools into the building trades. Pilcher, who has a lot of experience with nonprofit volunteer work, felt he could help with the housing shortage and, in the process, get high school students interested in construction.

His thought: What if high school students could build affordable housing while receiving training in building trades?

“I started by sharing my idea with faculty at Palomar College, a community college in San Marcos with a construction pre-apprenticeship program,” Pilcher recalled. They thought the idea had merit so he continued his research. “I also spoke with the Building Industry Association of San Diego (BIA). When I showed up, the entire staff of the BIA met with me. They were in the process of evaluating the Building Industry Technology Academy (BITA) program sponsored by the California Homebuilding Foundation. The BITA curriculum is offered to high schools who want to teach construction trades to their students.”

The BIA and the California Homebuilding Foundation are making real efforts to get industrial arts back into high schools, and this idea fit right in. Pilcher was invited by Mike McSweeney of the BIA to visit one of the schools participating in the BITA program. “I visited a school and spoke with the teacher. We walked around the shop site and saw little shower-stall-size rooms that the students were building to practice their framing skills. After the practice projects were finished, they were torn apart and the materials were either reused or thrown away. I asked them if they would like to build real houses instead of practice projects. I said: ‘How about building something you don’t throw away when you’re done?’ They loved the idea and I came away from the visit with the impression that it could work. That there would be an appetite for the program in schools.”

The visit inspired Pilcher to continue his efforts developing the project. “I was sending emails all over San Diego County to high schools that had wood shop programs or some kind of trades class like industrial arts or engineering. I was blasting emails all over to any contacts I could find,” he said. Most schools did not respond or weren’t interested.

But then his email landed in the right inbox. “The San Marcos High School engineering teacher got my email and forwarded it to the wood shop teacher. The wood shop teacher forwarded it to the head of The San Marcos Promise [https://www.thesanmarcospromise.org], a non-profit organization that provides students in the San Marcos Unified School District the tools and resources to plan and prepare for their futures beyond high school,” he explained. “The Executive Director of The San Marcos Promise, Lisa Stout, loved the idea and reached out to me. The 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization was looking for more ways to connect education, business, and industry leaders to impact student futures and really wanted to help provide real-world exposure and opportunities so students have a better sense of self, purpose, and direction for their futures as they move into their adult lives.” San Marcos High School adopted the BITA curriculum and started a building class, and The San Marcos Promise became the fiscal sponsor for the Warrior Village Project at the school.

Pilcher’s friend, architect Michael E. Robinson, volunteered to draw up plans for an ADU (Accessory Dwelling Unit). Robinson designed a 400 sq. ft. cottage, which would be built in two halves on the high school campus. Although the ADU would be built off site, in a Factory-Built Housing environment, it was designed to comply with state and local building codes for stick-built houses.

“Everything came together,” said Pilcher. “We had the plans. We started receiving donations of lumber and other materials, the curriculum was in place, and we got buy-in from the school board.” In September 2019, students at San Marcos High School, the biggest high school in the county with an enrollment of nearly 3,500, began building the first two cottages. “There were 23 students in the class, so the instructor, Chris Geldert, wanted to build two houses; he didn’t want the students bumping into each other trying to work on only one house. Mike McSweeney and Jon Hill and Alan Jurgensen from the Association of General Contractors Apprenticeship Program supervised the kids during the framing phase.

“Our house is kind of different,” explained Pilcher. “It’s modular, and is built off-site like factory-built houses. Factory-built houses are regulated differently than stick-built houses that are built on-site.” In California, the design and construction of a factory-built house is controlled by state approved third-party agencies. The design and construction of a stick-built house is controlled by local building departments. In a highly unusual arrangement, the County of San Diego agreed to review and approve the building plans and do inspections during off-site construction at the school.

The students worked on the houses from September 2019 until March 2020. “When the pandemic hit,” Pilcher said, “they had already done a lot of work on the houses.” The framing had been nearly completed, and the plumbing and electrical work had been started.

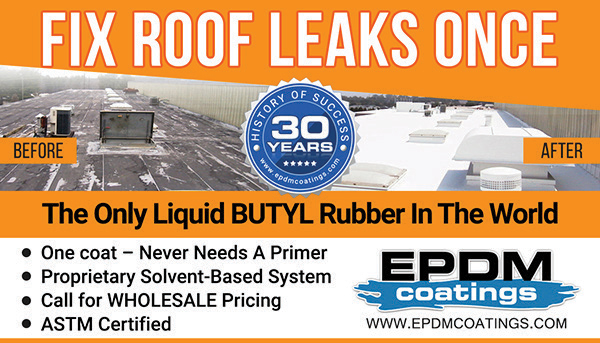

Boral Steel® donated the roofing material for the first two Warrior Village Project cottages. The company provided training, tutorials and mentorship for the roof installations while making sure the steel cutting and bending equipment was available to do the job. Installed over 30-lb. asphalt saturated felt by a team of volunteers, the lightweight stone-coated steel roofs are considered “cool roofs” and installed creating Above-Sheathing Ventilation (ASV). The metal roofing material delivers high total solar reflectance and high infrared emittance, keeping homes cool and saving energy by re-emitting most of what solar radiation is absorbed. Photo courtesy of Boral Steel.

While the students were away, volunteers kept working on one of the cottages. Volunteers also built the foundation for the first house with donated concrete, lumber and rebar. “AGC instructors and two teams of Navy Seabees built the foundation and trenched for the utilities two weekends in a row,” explained Pilcher. The first of the cottages was moved to its permanent site and is now nearing completion. “The outside is basically done. We’re finishing the inside now.” The Palomar College Departments of Architecture, Cabinet and Furniture Technology, and Interior Design are providing architectural and interior design support and building custom cabinets for the cottages.

One of the unique aspects about the Project is it’s not about building ADUs to place here and there. Its goal is to build enough compact, highly efficient homes to populate pocket neighborhood communities designed to house veterans in need, with each village comprised of 12 cottages and a community center.

“The biggest challenge is finding places to put the houses after they’re built,” said Pilcher. While the challenge of finding a location for the first village of ADUs hasn’t been solved yet, the efforts to house homeless veterans continues.

“Our first cottage was placed in the backyard of a house owned by Wounded Warrior Homes, a local nonprofit based in San Marcos that operates three homes in San Diego County. They have 13 bedrooms in three houses and can accommodate up to 13 veterans at a time.”

The cottage will provide an additional bedroom and serve as a transitional home. “Wounded Warrior Homes has found that some veterans don’t do well when they leave a group home and go out on their own,” Pilcher said. “Many guys entered the service out of high school and have always lived with someone. So instead of going from a group home into an apartment on their own, they’ll live in the cottage for a while to get used to living alone. It has a kitchen, bathroom, and bedroom, and plumbing for a washer and dryer. We’re hoping that by going through a transitional living phase alone in our cottage they will be more successful when they do move out on their own.”

The Warrior Village Project is a collaboration of building industry trade groups, nonprofits serving veterans, high schools and community colleges, business and private donors, and private citizens. Once the Project is fully up and running, these groups will all work together to provide affordable, permanent housing for homeless veterans while training the next generation of home builders. The mission is still in its infancy, but it has the potential for housing veterans in need and providing inspiration and guidance for youth who may do well in the skilled trades.